In 2018, the Bologna-based cultural association Hamelin published a monograph on my work, part of their Oblò series. One of the contributors was my friend and colleague Sophie Blackall, who wrote one of the funniest and loveliest things anyone has ever written about me (she has probably regretted it since). The book, of course, is in Italian, including Sophie’s piece. With Sophie’s permission, I’ve decided to share it here in its original English.

In the early days of sharing a studio, Sergio held out his fist. Neither of us is a natural fist bumper, so I was momentarily confused. Instead he dropped a whole walnut into my hand.

Tak! he said.

This is Sergio in a nutshell: surprising, unconventional, funny, endearing, generous and drawn to small, lumpy things.

Our studio is in an old textile factory in an industrial neighborhood of Brooklyn, flanked by a festering canal. There are four of us in the large, sunny room. Sergio’s corner is bright under skylights which sometimes drip when it rains. On those days his corner is shrouded in plastic sheeting, like an old house whose occupants have left for the season.

On sunny days his shelves reveal a collection of treasures given to him by friends, found on the street or bought on eBay. There is a row of unpainted wooden birds in varying sizes. Ducks, chicks, swans, sparrows. There is carved bear whose head opens to reveal an inkwell. Sweet, sad, orphaned stuffed toys huddle together in a corner. On the walls are a collection of vintage postcards of The Mystery Spot, (a gravity defying Californian roadside attraction), a Saul Steinberg print, an Arnold Lobel drawing and a photograph of Sergio, his daughter, Viola and Maurice Sendak.

There are piles of books and piles of papers and piles of drawings, all of which might slide, at any moment, to the floor. (My own space is FAR messier, so I am in no position to judge.) On his desk are medical specimen jars filled with suspicious liquid, actually diluted watercolor paint. There are mugs of pencils and brushes, bottles of india ink and a scattering of discarded nibs. Sergio himself was once described (by an enamored librarian), as dressing like an unmade bed. But the drawings made in this rumpled space are meticulously neat. His pen and ink lines are as fine as any I’ve ever seen. He works on several illustrations simultaneously, balancing them precariously on every available surface, but it has never ended in disaster, (except for that one time with the spilled ink, the only evidence of which is a few tiny black splatters on the far wall…) He paints swiftly, with enviable confidence, seemingly without hesitation and the stack of finished pages towers impressively. The paper, gently buckled from watercolor washes, looks like mediaeval parchment.

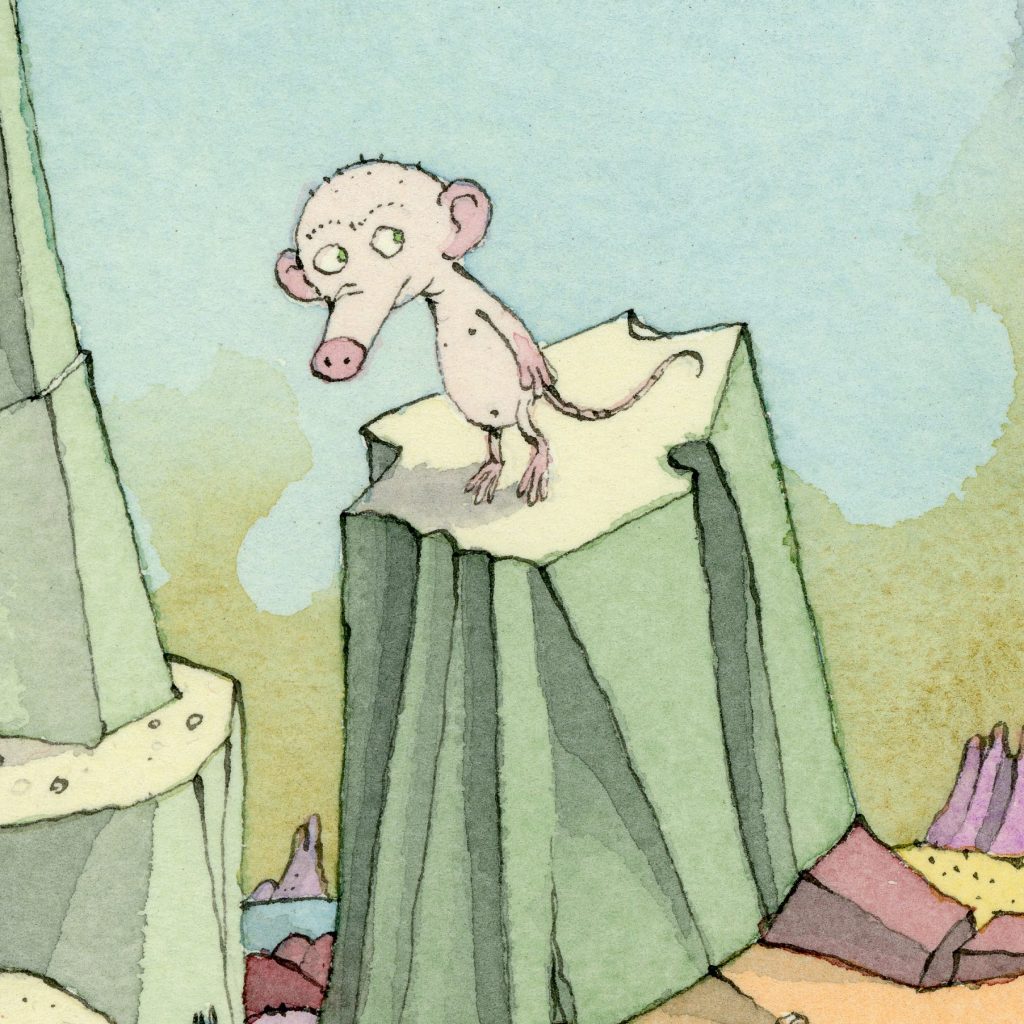

Sergio is not plagued with indecision in his work the way the rest of us are, because he is painting a well-defined world. Each book stands on its own, but the characters populate a similar landscape. His illustrations are instantly recognizable for their candy colored mesas and buttes and chalky cliffs. Their pink billowing clouds, stick-like trees and faceted rocks. Their unearthly plants. The perfect geometric tiled floors of their empty rooms.

You can imagine the characters from his many books might bump into each other along one of his pebble strewn paths, or find one another peering into a pastel gorge. They might all converge upon a rustic hillside tavern for soup; a party of two mice, a duck, a rabbit, an assortment of melancholy birds, a fox, a weasel, a mole and his grandmother. Not to mention sea monsters, furry snakes, one-eyed fish and the fellow I think is Sergio’s alter-ego, a dear, small pink person, with an elongated piglet’s snout, sticky-out ears, droopy limbs and a rubbery tail.

Speaking of soup, we eat lunch together almost every day in the studio. Recently Sergio carried a large bowl to the table, filled to the brim with soup. It was thick and hearty (literally). He dipped his spoon to retrieve a small round lump.

“You know what this soup is called?” he said, gleefully. “Belly button soup!”

The meat in the soup was sliced chicken hearts. Each slice did indeed resemble a navel, and we, the more squeamish at the table, shuddered. Sergio has an affinity for the grotesque, but somehow he makes it adorable. His books are filled with indescribable lumpy, hairy, fleshy, tumorous, protuberances. They grow from alien plants or roll around under tables. They are unsettling and hilarious and beautiful and repulsive. Sergio never draws human beings, but I think these disembodied lumps are as close as he gets. It is as though he is acknowledging our very worst bits, the most embarrassing parts of our bodies. But he treats them with fondness, putting them on display — albeit lurking in corners, or poking out from under a rug.

Children’s books have become awfully sanitized in recent years. We are afraid of offending parents or librarians, school teachers or book sellers. We are not really worried about children. We know children are unlikely to be offended by the things objected to by the gatekeepers. Sergio’s books are stubbornly and wonderfully unsanitized, and adored by children and the best grownups. He has made his own world and he makes his own rules. Occasionally a concerned publisher might ask him to put a lifejacket on a duck, or clean up some shards of broken glass in case an illustrated chick might cut his illustrated foot, but they usually, wisely concede the point.

Sergio Ruzzier’s stories take place in a dreamy world which is timeless — familiar and comforting but with hints of uncertainty. Beyond that buxom hill might lurk a ravine. His protagonists, in whatever form they take, are small children; like newly hatched birds, they are vulnerable, demanding, contrary, funny, melancholy and incredibly endearing.

But whatever small trials they endure, we know they will come safely home to soup.

With floating belly buttons.

Sophie Blackall