Two Mice made it into three best-books-of-the-year lists!

I mean four!

Sorry: five!

Two Mice made it into three best-books-of-the-year lists!

I mean four!

Sorry: five!

Julie Roach writes on the Horn Book:

Using only two-word phrases (“One house / Two mice / Three cookies”) and a simple repeating number pattern (one, two, three; three, two, one; one, two, three), this clever book (with an extra-small, preschooler-perfect trim size) creates a fast-paced adventure for listeners and new readers alike. Expressive, mildly mischievous pen-and-ink illustrations in soft colors develop details and drama that the words leave out. For instance, in the pictures, when the two mice “share” three cookies, the spotted mouse gets two cookies, while the plain mouse, miffed, gets only one. Before long, the mice venture out to sea (“Three boats / Two oars / One rower”), and this time it’s spotted mouse who does all the work, while plain mouse takes it easy in the boat’s stern. Soon the situation grows dire — “Three rocks / Two holes / One shipwreck.” They nearly become a raptor’s dinner before managing “One escape.” The two work together as a team after this near- disaster, and “Three carrots / Two onions” lead to a final nourishing “One soup” that both mice are happy to share — equally. Sometimes the pattern leaves the reader with practical questions: how did “One nest / Two eggs” hatch into “Three ducklings,” for instance? But trying to fit together all the pieces is part of the fun, and the book’s creative focus on pattern in plot leaves plenty of room for readers’ imaginations to play a strong role.

Kirkus says:

The deceptively simple counting story of two mice, their adventure, and friendship. One morning in Ruzzier’s imaginative and colorful world, two mice wake to explore. The tiny window above the bed beckons: water, mountains, and sky are waiting for these two. Starting before the title and ending on the copyright page, minimal text says all that is needed: “One house / Two mice / Three cookies. / Three boats / Two oars / One rower. / One nest / Two eggs / Three ducklings.” New readers will soon notice the number pattern and slow down to see how the droll illustrations extend the story. For instance, the mouse with one cookie has an angry expression and a rather tightly curled tail, while the loose-tailed mouse looks gleeful as it chows down on two cookies. The sunny rowboat scene is not so sunny for the mouse who has to manage the two oars. By the time the two buddies return to their home, all is forgiven when the delicious soup is served. (And, in a visual nod to Sendak, it is clearly “still hot.”) The small trim size and careful attention to details give this book enormous appeal; the decorative floor tiles, ornamental feet on the kitchen table, and mismatched stools fit right in with the red hills and ever changing sky. The simplicity of the text means that the earliest readers will soon be able to pick it up and will return to it over and over. One story. Two mice. Three cheers. Lots to love.

Here’s the jacket of the forthcoming Japanese edition of A Letter for Leo, published by Mitsumura (which already published my Amandina a few years ago). The blue band is the obi, the traditional paper strip that wraps the book jacket. Yumiko Fukumoto translated the text, as she did for Amandina and The Room of Wonders. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

I wrote this piece for this year’s illustration issue of The Horn Book. They graciously let me post it here as well.

I don’t like to experiment.

I know it sounds pusillanimous, but I’m just being honest: I don’t like to experiment because I am afraid of failure.

But at least two times in my life – at the very beginning of my artistic life – I found enough courage and determination to take risks. I was a fearless teenager then.

Being already passionate about picture books and comic strips – in particular those of Maurice Sendak, George Herriman, Elzie C. Segar, and Charles Schulz – it was clear to me how important would be to master pen and ink, if I wanted to be in that business.

Each of those artists had a very sophisticated and personal way of using the pen, and I wanted to find my own.

I remember going to the stationary store to buy my first two nibs, one very flexible and the other stiffer; then returning home and try them on the paper, keeping my hand from trembling; realizing I had to go from upper left to lower right to avoid; understanding how different pressures produce different lines; learning what kind of paper had the best surface for the kind of line I wanted to make.

In time, I did find my own way with pen and ink, which became my favorite and, for a few years, my only way of drawing. Most comic strips, at least the dailies, were in black and white, and I knew that even Sendak’s illustrations for Little Bear – a crucial source of inspiration for me – were colored mechanically. Because of all this, I didn’t think the lack of color in my drawings would be an obstacle in my future career as an illustrator.

Of course there was a hidden reason why I didn’t use color: the fear of failure. I had a fascination for Hieronymus Bosch, medieval frescoes and illuminations, so how could I not realize how important color can be for an artist? In fact, I had timidly attempted one or two small acrylic and a few oil pastel paintings, with very disappointing results, at least according to my overpowering superego. Those painful experiences kept me from seriously trying for years.

Once I became more conscious of the necessities of a professional illustrator, I couldn’t hide anymore, and had to face the challenging task of finding myself a method to add color to my pen drawings.

The most natural way to do that is watercolor, and so one day I went to an art store, bought a few half-pans of Schmincke watercolors, a brush or two, some Arches paper, and began testing the technique and my own resilience. For what concerned the techniques, I was set.

Maybe one day I will venture into buying a new kind of nib, or a new brand of watercolors, or even be audacious enough to try a paper with a slightly smoother surface. Who knows. For now, more than twenty-five years later, I’m still recovering from that initial double stress.

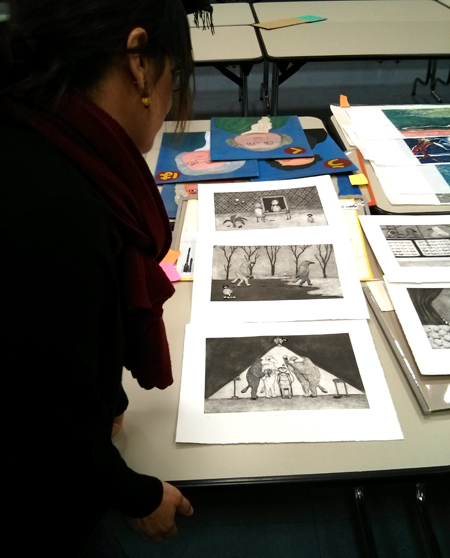

Here are my five drawings that were selected for the upcoming 2014 Bologna Children’s Book Fair’s Illustrators Exhibition. The show will be at the Fair, and then travel to Japan for a museum tour.

The Bologna Children’s Book Fair’s website just posted one image for each of the illustrators selected for this year’s edition.

Here are a few of my personal favorites:

Here’s Anna Castagnoli‘s third post on her experience on being a judge for the Bologna Children’s Book Fair’s Illustrators Exhibition. I apologize for any shortcomings in the translation, which would be solely my fault.

If you want to see the original post in Italian, go to Anna’s blog, “Le figure dei libri.”

Day 3

The large hall was changing appearance; we were now moving around fewer tables. Some had been cleared to leave room for the final selection. In the back, staff members were carefully placing in folders the works discarded the previous days.

The exhibition was to include about eighty illustrators. Among the 160 piles survived from the earlier selections, we had to choose roughly seventy (ten, the ones with four stickers on, had already been put aside). We began with the discussions: the job of a judge is not to have opinions, but rather to translate into clear language every little thought, taste, or feeling.

The level of the discussion was very high. We had persuasive arguments, which we were sharing with passion. We were all so good at defending our ideas, that we ran the risk of getting stuck. After discussing the third work, we decided to take a break. Isabel Minhos found the right words to get us started again: our goal was not make one’s opinion prevail over the others’, and it was not a tragedy if we eventually had to leave out one judge’s favorite illustrator. We could not have our personal dream show.

That’s when I understood that we were a group, and that we were to select the show as a group, in a way putting aside our selves. The exhibition would have been precious because it would mirror something that none of us could have predicted before our getting together. And that’s how it went.

An illustration changes when paired with a text

We started to spread the drawings on the floor and make up stories based on them, to see if those images would have worked in a kids’ book, knowing that a text changes considerably the perception of an image. Sometimes there was no way to see what story would have worked with the the images: “They’re too much like postcards,” one of us would say, “rather than moments of a possible story.” “Could they be paired with a poem?” another would ask, without being too convinced. “What if we moved these to the non-fiction category?” “No, they’re not descriptive enough. We can’t. Let’s go to the next.”

An illustration is not a poster nor a painting to be hung on a wall.

The images had to have the right qualities that make an illustration an illustration: not a poster, or a painting for a museum, or a picture for a trendy magazine. In a book, each single image is a moment of the story. In a way, a book illustration needs to be an incomplete passage (the rest of the illustrations in the book will complete it).

Of course, the language of the children’s book is changing. The “new wave” style about which many have complained in the past years was not solely the jurors’ fault. It was really difficult to find, among those thousands of images, a traditional narrative style. We had to find these characteristics trying to decipher new languages. We also had to evaluate illustrations expressed in “languages” we were not familiar with (in works from Iran, Japan, Korea, China, Argentina…)

We had to take the time to understand all that, and we did. Sometimes we would read the title on the back of the drawing, to get some help. We discussed a lot. There was one quality that we all considered essential: an image had to “invite you in.”

There were images one had the feeling of entering into (or falling into, since we were looking from above). Even when they had flat field of color and no perspective, they called us in and get us involved.

The world represented had its own rules: they may have been absurd, but they were coherent. Other images stayed on the paper, without creating any world. More than anything, we didn’t feel they had a soul, to use Kitty Crowther’s expression. From a stylistic point of you, it is difficult to pinpoint such mysterious quality in a drawing, but here are a few focal points singled out by Kitty, Isabel, and Errol:

– Quality of the technique

– Stylistic consistency

– Richness and diversity of the composition

– Honesty (one thing is being inspired by other artists’ work; another is copying. We would get rid of anything we would consider “already seen,” or cliché)

– Ability to experiment and research new languages

– Storytelling

– Ability to capture the reader: freshness, energy; ability to surprise, involve, even disturb the reader

– Ability to see the world from a child’s point of view and his or her need of adventure, exaggeration, deep feelings, with a specific regard to gender; we asked ourselves if there is a difference in the way a boy and a girl perceive illustration: do boys need more adventurous, less embellished images? [I don’t think so! S.R.]

– A sound content: one that doesn’t try to hide or edulcorate the truth

– Attention to the relationships between the characters

We had decided that each of us could use one wild card, which we could use in order to have one illustrator in the show, even if the other three judges didn’t like the work. We saved it for the right occasion. It was more fun to explain one’s reasoning and try and make the others change their minds. Often, we would succeed. Once one found the right words, that’s it! we would all get it. The very way we looked at an image would change. It was incredible, for me, to learn so much. The other judges as well had the same feeling of growing and learn to shift one’s point of view.

It was good to present the “yeses” to the organizers or to Deanna, who were always waiting behind us. “Is this a yes?,” they would ask, with hope. “Yes, it is a yes!” we’d answer, with great relief, almost as we had just helped a baby be born. Little by little, the table for the accepted works was getting filled with images.

Something that never tires you; that slips away…

Many images to which we eventually said “yes” to had this quality: we never grew tired of looking at them. We would gladly go back to them, again and again, to wonder about them. They were not necessarily perfect, or beautiful. They could even have flaws. Sometimes, we didn’t even really like them. But they had something that we couldn’t quite grasp, that gave them a vibration, an intensity, a strength that never wore out; in that case, we would say “yes.”

Plagiarism

One ground for exclusion was when the presence of another known illustrator was too obvious in the image. We found: 3 fake Géraldine Alibeu, 1 fake Maurizio Quarello, 1 fake Quentin Blake (for a moment we thought it was Blake himself who sent those drawings in in order to test us), 2 fake Beatrice Alemagna, 1 fake Isabelle Arsenault, 1 fake Jockum Nordström, and 2 fake Wolf Erlbruch from Germany.

For what concerns other continents, it’s possible that some plagiarists passed through. But for the Europeans, we felt quite secure.

But… Suddenly, five giant little girls pop in front of our eyes. They are dancing, or more simply put, they stand there. They have one eye, like cyclops. They are sweet, nice, enigmatic. The technique used to create them is very similar to Beatrice Alemagna’s: similar collage method, similar colors, similar style. But in those little figures there was something original and new. We decide we want them in the show. Soon after, we ask each other: who’s going to tell Beatrice? The thing is, we thought that it was not too bad to copy a little, if what you are able to say is new and original.

Digital illustrations

The percentage of digital images was quite low, maybe 10%. For the next editions of the show, keep in mind that the Fair prefers original works, since the primary goal of the selection is an exhibition. Obviously, if the quality was high enough, we didn’t discriminate. The problem was that most of the work was poorly printed, on cheap, thin paper. If you want to submit digital pictures, print your pieces on good, matte paper, from high-res files. And do include your preparatory drawings or sketches.

Previously selected illustrators

There were a number of illustrators who had been selected in the past editions. In a few cases, they won us over. In other cases, we wanted to make sure their work had evolved since the last time: if it didn’t, we wouldn’t select them, leaving room for new artists.

We skipped lunch, eating only a few chips from a tray. There was too much work to be done. I felt like I was bursting with joy: the critical work I was doing, the debate around the language of children’s book illustration is what I most love in my job. For once, I forgot that I get weak when I don’t eat.

In the next and last post I will tell you specifically of some of the work we chose and why we found that work innovative.

And that will be it.

Anna Castagnoli

One juror’s diary

Day 2: our criteria

(Click here to go to the original post in Italian.)

Second day

At five in the morning, in my hotel room, a thought woke me up: I was so excited to have been invited to Bologna, that I had completely forgotten what it really meant, for me, being the juror in such a prestigious exhibition. I tried to go back to sleep: no way. I was thinking about what illustration meant for me, and my blog, and everything that had brought me there. Thought after thought, I went back to 7-year-old me, as I was flipping through an illustrated book. That primitive, absolute marvel to have in those pages a world all for me, a world where I could live in, and go back to visit if I had missed something. The illustrated books had helped me. Childhood is not that happy kingdom that many people think. That was it: the real reason for me to be there was to defend precious images.

At 8 I went downstairs for breakfast. Kitty was already there, and I immediately started to talk to her about the importance of giving the children a true and profound culture (I was saying that to Kitty Crowther!, one of the most courageous illustrators in the world, the winner of the “Noble prize” for illustration…) and how big a responsibility we had as judges. I was sure that she was thinking, while staring at me, “this girl is nuts.”

Instead, she waited for me to finish, and then she began telling me her dream: she dreamed that it was us who were going to be judged as pastry chefs (!).

When Isabel and Errol joined us, we went on with the conversation. Isabel suddenly said, more or less: “We have to tell the kids about the things that are important to us; we should not create a culture that is custom-tailored.” Errol, pragmatically, talked about the importance of teaching the children how crucial it is to be able

to change point of view: this is the essence of creativity. The world of tomorrow will be saved by creative people, who are able to face the problems from different angles.

We were going back and forth between French and English. I was delighted by our harmony: I couldn’t hope for more exquisite colleagues.

We looked at the time: it was late, and the driver was waiting for us.

When we arrived to the Fair, we finished working the tables that were left from the day before. By now, the big hall felt familiar to me. The idea of spending another long work day made me feel that happy tiredness that you feel in your arms after doing physical work outside. But now with the knowledge of being better able to control gestures and emotions.

The definition of the criteria

When we were done with the tables, it was already 11 o’clock. The directors invited us to sit down, and take an hour to define the criteria by which we would judge the work. We were free to create our Exhibition, with no obligations or restrictions.

We looked at each other and we smiled: we practically already had our criteria. One word summed it all up: honesty.

We would favor the illustrations in which it was clear that the artists challenged themselves, trying to say something important for them. Something honest, personal, detached from any trend.

Errol pointed out how difficult it is to compare illustrations that were taken from books with others that were unpublished or done on purpose for the competition. We then decided to act as if we were editors, who receive mountains of different images: we would evaluate whether the images could give life to an illustrated book for children.

Roberta Chinni, the Fair’s director, explained to us that the Fair is for publishers of books for children aged 0 to 16. So, we would choose the best images for children aged 0 to 16, based on the honesty with which they were made and the level of innovation they brought to the international landscape. (If you think that we rejected an illustrator who created five astounding illustrations, but practically identical to what a 19th century illustrator would have done, you’ll understand the importance of the criteria.)

Another criterion was that the technique had to be good, but not overrefined at the expense of the message’s spontaneity.

Lastly, we would favor, above a level of quality that was clear to us all, images in which we felt that the illustrator had taken a risk.

We would define more criteria during the actual selection.

Before lunch, we answered a few questions posed by the students of MiMaster, the illustration school based in Milan.

At lunch, we had the pleasant surprised of being joined by Satoe Tone, who was there to work on a book with the Fundación SM (the SM award gives 30,000 Euros and the possibility to create a book that is presented at the next year’s Fair. Satoe won the prize in 2013). She is delightful.

After lunch, the organizers gave us a bunch of Post-Its of four different colors, one color for each of us.

The first survey over the 200 plus illustrators still in the run was do be done solo, expressing our judgement placing a full sticker if we were 100% sure; half a sticker if we had doubts; and no sticker if we were no longer convinced by the work.

At the end, we would see which images had four full stickers and hence already chosen for the exhibition; which ones we would have a conversation about; and which none of us felt like discussing.

With my great surprise, having the criteria now clear in my mind changed the way I looked at them. It was no longer “I like it,” but: “Was the illustrator honest, or he just wanted to please?” and: “Would have I liked this when I was eight, or thirteen?” and: “Is there something new in this work?”

It was important, and difficult, to try to identify sincerity in languages and styles that were so far away from the European way, since there were 191 countries represented.

About ten illustrators, or maybe fewer, received four full stickers. Those were images that convinced us without hesitation from day one.

We laid them on two long empty tables. How depressing! It was the smallest ever illustration exhibition! We felt better when we took a look at all the piles with three Post-Its: another ten or so. Only twenty illustrators we all quite agreed on. And the others? How could we get to eighty? But it was 7 P.M. and we were exhausted. I was dreaming of a hot shower and dinner. Who knows me knows how my face looks like when I’m hungry. For my joy, we were treated as royalty: as soon as I was about to turn pale, Deanna Belluti would arrive with a tray, asking casually: “who wants a pastry?”

If I have to choose one illustration among the ones that got four Post-Its, as an example of our unanimity, I’d pick this one by Arianna Vairo, which you’ll see at the show. The power and the freshness of her work is impeccable; her courage and honesty, out of discussion.

In my next piece, I will tell you about the third day, which was the most fascinating: that’s when we had to start seriously and passionately discussing the “why yes” and “why no” for each group of illustrations.