Category: Blog

Fox & Chick: End-of-the-Year Lists!

by •

One cannot say Fox & Chick: The Party and Other Stories went overlooked! I am happy to report that the book made it into a bunch of end-of-the-year “best” children’s books, including:

NPR Best Books of the Year

New York Times Notable Children’s Book

Boston Globe Best Book of the Year

Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year

School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

The Horn Book Magazine Fanfare Best Book of the Year

Chicago Public Library Best Book of the Year

The 2018 Nerdies: Early Readers and Early Chapter Books

And I might be forgetting a few…

Two stars and more for Fox + Chick

by •

“Three stories well suited to both reading newcomers and not-yet-reading listeners. (…) Collectively, these three stories create a profile of an entertaining odd-couple friendship that, if given a few more outings, could make a Frog and Toad–like impression on the picture-book and easy-reader worlds.” —The Horn Book Magazine, starred review

“A winning choice as a confidence booster for children just learning to read.” ─School Library Journal, starred review

“Brilliant. Sure to be a favorite for reading aloud or as an easy reader.” —Imagination Soup

“Calm Fox and irrepressible Chick make a delightfully funny duo, and Ruzzier captures that perfectly in text and expressive, relatable illustrations. With vast appeal, this series debut will delight younger kids.” —Books to Borrow, Books to Buy

“This charmer blends graphic-novel and early-reader conventions for young readers not quite ready to tackle chapter books.” —Booklist

“There’s an easygoing, reassuring rhythm to the storytelling, and the simple text and sunny colors should engage nascent readers.” —Publishers Weekly

“A fun, simple, yet sophisticated collection about a friendship between two very different characters.” —Kirkus Reviews

If Chick was not annoying

by •

In PW’s otherwise favorable review of Fox + Chick, the author questions the two friends’ relationship: “The root of their friendship remains an enigma—why does Fox tolerate such an annoying friend?” I’m happy to rethink the three stories making Chick not annoying:

– The Party (to be renamed The Bathroom)

Fox is at home, reading a book. Chick arrives and asks if he can use Fox’s bathroom. Fox says yes. Chick uses the bathroom and then leaves.

– Good Soup

Fox is picking vegetables to make soup. Chick follows Fox around. Fox makes soup for both of them. They eat the soup.

– The Portrait (to be renamed The Landscape)

Fox is on a hill to paint a landscape. Chick arrives and admires Fox’s talent. When the painting is done, they walk together down the hill.

To see the original version of the stories, you can get the book at your local bookseller or on Indiebound.

“Vita di uno strano signore” or, “Life of a strange gentleman.”

by •

About two years ago, the Associazione Culturale Hamelin invited me to have personal exhibition of my work in their beautiful rooms in the center of Bologna. Flattered but equally scared, I accepted the invitation. The show, titled “Vita di uno strano signore,” opened last month during the Bologna Children’s Book Fair and will stay up until May 4.

Here are a series of pictures from opening night, taken by Hamelin’s own Emanuele Rosso. I will post soon a different series of pictures without visitors, to better illustrate what was shown.

Thank-you to all who helped to organize the show and to everyone who visited.

S.R.

The most important moment of the preparations: stuffing the tigelle.

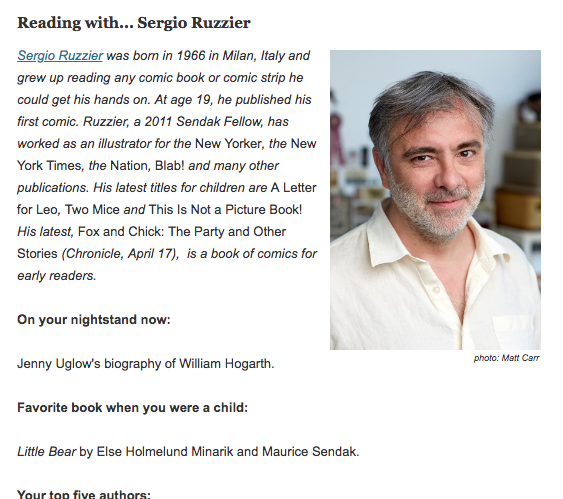

Shelf Awareness Interview

by •

After an exhausting wait, you can finally learn about my reading habits in this interview with Shelf Awareness.

Helpful Books for Disturbing Times

by •

Here is a small selection of children’s books that I personally find helpful and perhaps hope-inducing without trying to hammer a moral lesson into your head, which could be not only painful but counter-productive.

(The links are to Indiebound.org, but of course you can find or order these books at any other bookstore or library.)

Arnold Lobel

Grasshopper on the Road

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780064440943

Leo Lionni

Little Blue and Little Yellow

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780688132859

Tony Kushner and Maurice Sendak

Brundibar

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780786809042

Jo Hoestlandt and Joanna Kang

Star of Fear, Star of Hope

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780802775887

Tomi Ungerer

Otto: The Autobiography of a Teddy Bear

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780714857664

Ruth Krauss and Crockett Johnson

The Carrot Seed

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780064432108

William Steig

Amos & Boris

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780374302788

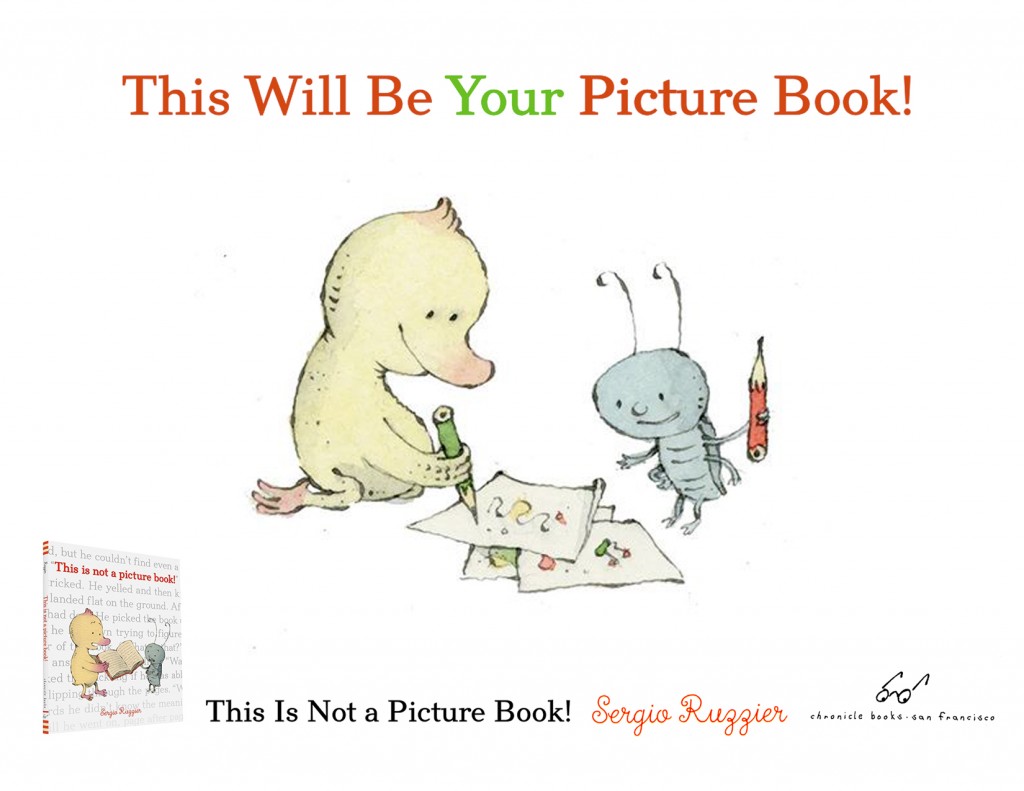

This Will Be Your Picture Book!

by •

Three Stars So Far

by •

Some reviews for This Is Not a Picture Book! have come out. As usual, Publishers Weekly and Kirkus were the first ones, and they both gave my new book (my first with Chronicle) wonderful, starred reviews. More recently, School Library Journal published their own starred review.

This isn’t a book about books; it’s a book about learning to read. A duckling with a pink beak picks up a fat volume and discovers, in the irritated comment of the title, that it has no pictures. “Can you read it?” asks his sidekick, a bug. “I’m not sure,” says the duckling. “Words are so difficult.” In luminous watercolors, Ruzzier (Two Mice) shows the duckling and bug crossing into a strange, many-colored world, where unfamiliar words are represented as odd machines, blobby shapes, and bizarre creatures. When the duckling stumbles on a word he knows (“bee,” “flower”), its recognizable image pops up among the mysterious ones. Duckling and bug wander through the ever-changing landscape of reading—“There are wild words… and peaceful words”—before landing cozily in bed. Ruzzier’s story offers gentle empathy for kids tackling this intimidating task. Observant readers will note that the endpapers represent learning to read, too; the initial pair retells the story as a beginner might see it, with most of the words scrambled, while the words of the final endpapers read clearly—and no pictures there, either.

And here’s what they think at Kirkus:

A metafictive delight of a picture book.

Alice would be pleased: despite Ruzzier’s title, there are plenty of pictures and ample conversation in this picture book. The titular book within the book, however, is illustration-free. This initially causes distress for the duckling protagonist (who oddly has a bellybutton, but that’s beside the point) who finds the book in the spreads before the title page. When a bug appears and asks, “Can you read it?” the duckling gives it a try. In a brilliant feat of page layout, the recto depicts a green landscape encroaching on the verso, with a log laid across a chasm as a bridge to the white space on which the duckling and bug stand. Their walk across the log is a visual metaphor for the duckling’s successful decoding of the text in its pictureless book. Whole worlds open up to them as the duckling reads aloud. Illustrations depict these worlds evoked by “wild words… / and peaceful words,” and the duckling ultimately declares that “All these words carry you away.” The satisfying conclusion is an affirmation of the transformative power of reading. In one outstanding design touch, the front endpapers tell the not-a-picture-book text in garbled type with transposed letters that one must strain to decode, while the text is clear in its entirety on the back ones.

School Library Journal:

In this winsome examination of the power of words, a little duckling is delighted to find a red book lying on the ground. “Where are the pictures?!” the fuzzy yellow bird exclaims in dismay upon opening it up. The duck flips through the pages, scanning the plethora of print, and begins to recognize some of the words. His interest and enthusiasm flourish as he continues, reading words that are funny and sad, wild and peaceful. His imagination takes off, and along with his tiny cricket friend, the duckling is swept away on a fantastic adventure. He tells the little insect, “All these words carry you away…and then…they bring you home.” The straightforward tale is enhanced by endpapers featuring lines of text, which are jumbled in the front and placed in order to relate the duck’s story in the back. The eclectic pen, ink, and watercolor illustrations add color and energy to the narrative. At first, the pictures are set against a canvas of white space and then slowly expand as the duck begins to envision scenes with each additional word he reads. One of the final spreads portrays the duck and his friend safe at home in his bedroom, which contains a shelf crammed with books.

I can’t wait to know what the others think!

Picture Book Thoughts From Bologna

by •

This year I was one of the five jurors of the Bologna Children’s Book Fair Illustrators Exhibition. In the beautiful catalogue published by Corraini, I was asked a few questions on creating picture books and more.

The five jurors: Klaus Humann, Nathan Fox, Francine Bouchet, myself, and Taro Miura.

You have said in the past that there are so many obstacles and taboos when creating children’s books, that you run the risk of censoring yourself. How do you avoid self-censorship?

I was specifically referring to the U.S. market, where all my children’s books so far have been originally published.

I consider myself fortunate to have found such a fertile ground for my ideas and my style, and I doubt that I would have been able elsewhere to make my passion for picture books into an actual profession. I am very grateful to the editors who saw potential in my work, beginning with the unforgettable Frances Foster.

There is, of course, the other side of the coin. Compared to what gets published in other Western countries (Germany, for example, or France, or, perhaps to a minor degree, Italy), American books for children tend to be very tame. There are glaring exceptions, of course, but generally speaking you don’t see books that deal with issues that are considered too mature for the audience: death, sex, war, violence, depression, and so on. When books on such themes do get published, they tend to be heavily weighed down by a predictable message, and illustrated incompetently. There is the widespread belief that children need to be shielded from the reality of life. That, in my opinion, is a huge mistake, and is akin to lying. Of course I’m not suggesting that children’s books should include pornography or gratuitous violence, but if a story calls for it, one shouldn’t shy away from showing unpleasant situations. The risk of self-censorship I was talking about is always looming, and can be difficult to detect.

When writing a story, or drawing a picture, you do feel the pressure to deliver something free of possible controversy, or to make choices based on specific political agendas. But in order to produce the best possible work, the only pressure you should feel is the pressure to be true to your own voice.

When creating a children’s book, do you ever have a precise image of your ideal reader in mind?

Absolutely not. I don’t think of the reader at all. I believe that when writers think too much about who’s going to read their book, the result will be formulaic at best.

Which illustrated book would you have liked to have authored? Why?

There are so many authors and illustrators I worship and whose books I hold dear. In general, I’m drawn to unusual stories that are beautifully illustrated without trying to impress. I can’t stand authors who follow a trend and illustrators who want to show off without even possessing the appropriate skills. Warmth, sincerity, and irony are the main qualities I always look for in a book.

Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad stories are among the most profound, funny, endearing books I’ve ever read. The drawings perfectly match the tone of the text, at the same time melancholic and reassuring. William Steig, Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, Edward Gorey: they all have created wonderful books that keep inspiring and humbling me.

But if I have to pick one single book, it would probably be Wolf Erlbruch’s Duck, Death, and the Tulip. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s a death dance for children. It’s original, powerful, sweet, compassionate, sad, comforting. It’s done with such measure and good taste. I would be happy if I could produce something comparable to that book.